Praxis

Learning to Fly (and Flail): A trad climber's auto-ethnographic narrative from the sharp end of the rope

Hello friends! It’s been too long, but I’ve had a busy few months and have struggled to find time to write much here. I haven’t even kept up with my monthly music recaps, although I’m still updating the playlist. Either way, GRIM! Anyways, I’m going to try and get back in the swing of things. Hopefully, I’ll be better. To kick that trend off, I thought I’d post one of the assignments I’ve been working on the past few weeks. It’s not my best work, but it’ll serve as a means to get back in the Substack saddle. Enjoy!

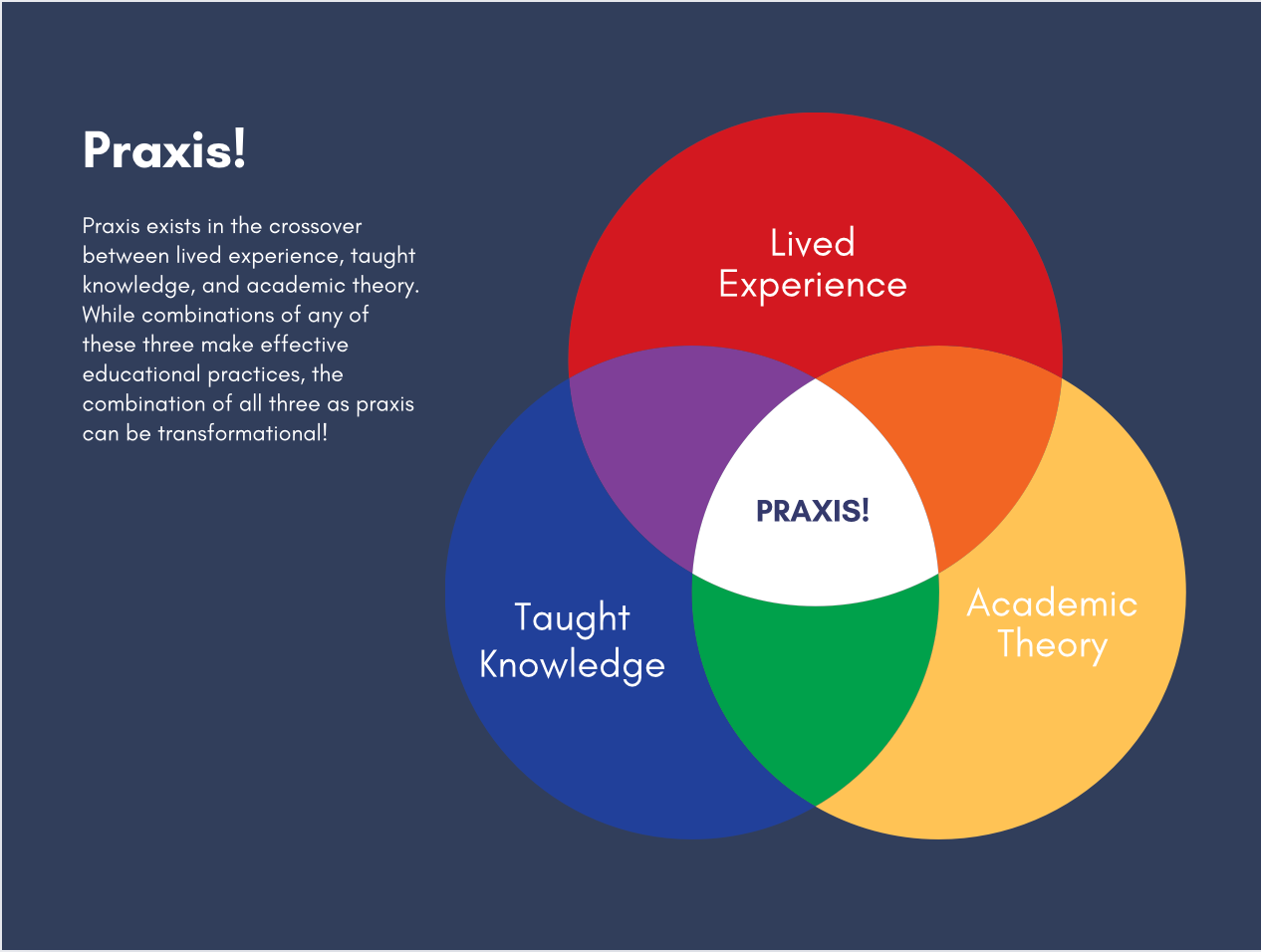

Outdoor education exists in the space between theory and practice. Neither is necessary for the implementation and understanding of outdoor ed, but using a combination of the two allows for educators to continue growing and improving as practitioners. Mahon and Smith(2020) call outdoor education the interplay between saying, doings, relationships, and the theory that informs all of these aspects [1]—not just a combination of theory and practice, but also a combination of the various roles and aspects that make up practice. In this context, a more appropriate word to be used would be praxis, which is explained by this Venn diagram! (self-made using Canva)

Praxis concerns experiencing events firsthand and reflecting on what happened, how you reacted, its interplay and relationship with theory, and using what you learn to inform your future experiences. Mary Breunig (2005) says that praxis is “reflective, active, creative, contextual, purposeful, and socially constructed” [2], and grows from an abstract idea—theory—that is then formed and understood by experiences and reflective practices. On top of this, praxis is always changing. Because lived experiences, taught knowledge, and academic theory are not static ideas, the praxis is constantly changing, as well. As the Greek philosopher Heraclitus once said, “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it's not the same river and he's not the same man”[3]. The implementation of praxis functions the same way.

In this assignment, I will be reflecting on my own praxis as an outdoor educator through the retelling of a vignette from my own experience as a practitioner, educator, and outdoor recreator. Tim Ingold sees stories as an effective means of reflecting on ones’ personal praxis, writing “…each story will take you so far, until you come across another that will take you further.” [4] This idea also supports the notion of praxis having historicity—it is always in a state of being, it is simply its depth and breadth that changes. Finally, rather than just reflecting on this story, I hope to be a diffractive practitioner [5], observing the interplay of praxis’ elements in the vignette, both in the moment and in the future.

Deep breath in. Deep breath out. Thoughts racing through my head: “Nuts? Yes. Cams? Yes. Draws? 12. Do I need these hexes? No.” Some jingling as I unrack the four pieces of larger passive protection from my harness. “Enough lockers? Yes. Sling? Dyneema and nylon, two 120s and a 240.” I take another deep breath and look up at the climb, thinking thoughts of self-affirmation. “Pull hard, you’ve got this.”

“You ready?” I ask my belay partner, checking that her belay tube is oriented correctly and the carabiner is locked.

“Yep, you’re good to go” she replies, taking a cursory glance at my knot and nodding approval.

“Ok, climbing.”

I shoot up the wall with no hesitation, climbing a fist-crack separating a pillar from the main rock face for about 6 meters, placing 2 cams as I make it to a ledge with a no-hands rest that allows me to prepare for the second half of the climb. As I shake out the wee bit of lactic acid that has started building up in my forearms, I look at the second half of the climb and try to collect my thoughts—it is much more vertical, the placements are not as obvious, and my heart starts racing. I push down the rising feeling of fear in my throat and call down, “Climbing, again,” as I start back up the route before I have any second thoughts.

About a meter off the ledge I place a good nut, then a cam a meter above that. I feel good. Dipping my hand into my chalk, I notice that if I move left I can follow a series of cracks all the way to the top of the face. I start left and after a few moves of traversing find myself at its start and am ready to ascend. I start up the crack and a few meters up get my right hand into a deep crimp, with a foot on a comfortable enough chip. I feel stable enough to try and place some gear. I unrack my set of nuts and as I try to find the right size of pro to fit into the faults in the rock that I’ve been climbing. “Nope, not the size 5.” A bit of faff as I thumb through the set to try a bigger one. “This size 7 fits, but it’s not great.” I double it up with a size 8 just above it. “Also not great, but two iffy placements equates to one good placement…right?”

I climb above my two dodgy nuts and grab a huge jug right the below the crux of the climb, it looks like I have to move my body position into a layback, a pretty reachy and committing move. At this point, I’m pretty pumped. My forearms are screaming, I can feel my too tight climbing boots painfully curling into my toes, and one of my legs start shaking as I think about potentially falling on the gear I have placed below. I take a deep breath, stare down the sidepull that I’ll be trying to grab, try to stop my quivering leg, and reach.

Slap. Yell. Pop. “Sh*t!” “F*ck!”

I missed the edge, overshooting it by a few centimeters. After my hand slapped the rock and failed to grasp the edge with my fingers, I started to fall—hence the yell. The pop was my most recently placed nut flying out of the crack as it unsuccessfully tried to stay wedged in the crack. The first expletive was my belayer’s reaction as she caught my whip and was pulled upwards by the force of my fall. The second expletive came from my mouth as I hung suspended from the nut that a few minutes earlier I didn’t trust.

“Are you all right!?” My belayer shouts up.

“Yeah, I’m fine. Can you lower me down to the ledge?” She obliges and once my feet are once again firmly on a solid surface I begin to try and process my first trad whip.

That was terrifying. One of my pieces popped. F*ckin’ hell, I do not want to do that again. I can’t believe I messed up that move. I was so close to the top. I bet that nut is absolutely glued in the crack now, have fun getting that out haha. Ok. Calm down, finish this climb.

“Ok, I’m going to try again,” I call down to my belayer. I moved through the same moves again, this time stopping to place more pro to replace the piece that popped. Hopefully this one will hold. Hopefully I won’t need to find out if it holds. I hang off the same jug I was on earlier, glancing again at my next hold and spotting the chalk mark I left just past the edge I was shooting for. I notice that one of my fingers is bleeding, I must have missed it earlier due to the adrenaline coursing through my body. I’m in no position to wrap it with tape now, so I’ll have to deal with it later. Once again, I take a deep breath and reach.

“C’mon, c’mon, c’mon.” I’ve grabbed the edge and shifted my body into the layback. I’m audibly talking to myself, urging myself to hang on, to keep going. I get my right hand into the crack, then shift my feet over. I bump my left hand above my right and swing my right foot around into crack, leaning and pulling to the left as I hold myself suspended above the ground, a meter below the top out.

“C’mon, c’mon, c’mon.” I eye the crest of the wall. Safety. Rest. Finish. Accomplishment. “Gaarrrghghhhgh!!!!” I yell as I reach for what I think is a jug. I’m wrong. It’s a sloper. “C’mon, c’mon, c’mon.” I’m trying my damndest to keep my hand on this angled face. My left foot starts to flail as it comes off its hold and my brain goes into panic mode. I dig my palm into the rock and slap my other hand onto the slabby finish to this climb. It sticks. I lean my chest onto the top between my hands, and start to shimmy my torso away from the edge. I feel like a beached whale. Finally, I’m far enough away to roll over. I’m safe. I topped out. I did it.

I’m soaked in sweat, exhausted, but still need to belay my second up. I take a few moments to catch my breath, then sling a tree, clove in, and shout safe down to my second. Over the next half-hour I belay her up the route (she took a while to get that nut unstuck), we walk off the back, and decide that we’ve had out fill of climbing for the day. As we start back towards the train station, I look back at the route and smile.

While this was an experience that I had recreationally, I think that it applies very well to the idea of praxis in an educational setting in that it offers the ability to analyse the experience from my self-defined idea of praxis: lived experience, taught knowledge, and academic theory.

Lived Experience: This was my first time falling on trad gear during a climb. I think that this was a beneficial experience for me in the long run for multiple reasons: some of my protection failed and some of my protection worked. In terms of the former, I know have to acknowledge that poorly placed gear will not always hold, thereby encouraging me to be cognizant and intentional about that aspect of my climbing. On the other hand, one of my nuts caught my whip, protecting me, doing its job, and keeping me safe. That is very reassuring and gives me the peace of mind to continue to push my limits and climb above protection on trad climbs.

Taught Knowledge: Most of the climbing skills I demonstrated in this story come from taught knowledge, either from instructors, books, or videos—how to tie into a rope, how to place protection, how to clip quickdraws, how to build anchors, different climbing techniques, etc. It is an extremely important part of climbing; it would be almost impossible to start trad climbing without first learning from certain forms of taught knowledge. While it doesn’t have as much of a role in this instance, it is still present in the experience., especially as I continue to learn more as a climber!

Academic Theory: Academic theory is present in almost every experience, even if we don’t recognize it. In this example alone, there are questions of risk management, ideas of comfort-zones, and even personal and social development that have all been examined in academic contexts. Was I climbing above my grade? How did that risk compare to the reward? I was definitely out of my comfort zone at points on this climb: did that positively or negatively impact my learning/development?

Ultimately, the idea of praxis is with us in all of our experiences. As a diffractive practioner and outdoor educator, it is my goal to identify its different elements, think about or research relevant theory surrounding the experience, examine how I can learn and grow from it, and apply it to future experiences I may encounter like I have done here.

Citations

[1] Mahon, Kathleen & Smith, Heidi (2020). “Moving beyond methodising theory in preparing for the profession”. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 20:4, 357-368.

[2] Breunig, Mary (2005). “Turning Experiential Education and Critical Pedagogy Theory into Praxis.” Journal of Experiential Education, Volume 28, No. 2, pp. 106-122.

[3] Heraclitus quotes, www.brainyquote.com/authors/heraclitus-quotes.

[4] Ingold, Tim. (2011). Being alive: Essays on movement, knowledge and description. London: Routledge.

[5] Hill, Cher (2017).“More-than-reflective practice: Becoming a different practitioner”. Teacher Learning and Professional Development, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 1 – 17.